Learning Drupal with the Janki Method

One of the best ways to set yourself up to succeed with Drupal is to adopt a habit of continuous learning. I’m sure there are plenty of ways to do this, but over the past 8 months, I’ve been using a system called the Janki method, and it has really served me well. This post is intended to explain what the Janki method is, and how you can use it to learn and retain Drupal information.

What’s the Janki Method?

The “Janki method”, is a technique for retaining the programming knowledge by using spaced repetition software. Space repetition can be used to learn anything from fractions to Farsi, and it’s also effective for learning Drupal.

Wait… spaced repe-what?

Basically, there’s a category of learning software called “spaced repetition software.” Think of it like flashcards, but smarter. These flashcards are designed with algorithms to adjust the repetition of facts so as to maximize your ability to retain the information. The algorithms are based on studies about long-term retention of information.

Anything you plan on remembering for more than a couple minutes requires repetition. Your current Drupal knowledge consists of the tasks you’ve performed repeatedly, like creating a new content type or writing a hook_menu implementation. But learning Drupal like this is inefficient because some tasks tend to come up a lot more frequently than others. With my work, I get a lot of practice adding values into the vars array and printing them in templates, but I already know how to do that. What I really need is repetition working with imagecache, multilingual, or other areas where my knowledge is fuzzy.

Enter Anki

Anki is an open-source spaced-repetition tool that you can use to make learning Drupal less random and more efficient. There are other tools out there (paid and unpaid), but I’ve been using Anki because it syncs across devices and it’s free. There’s a web version, and desktop version, as well as apps for Android and iOS.

Anki is an open-source spaced-repetition tool that you can use to make learning Drupal less random and more efficient. There are other tools out there (paid and unpaid), but I’ve been using Anki because it syncs across devices and it’s free. There’s a web version, and desktop version, as well as apps for Android and iOS.

How it works

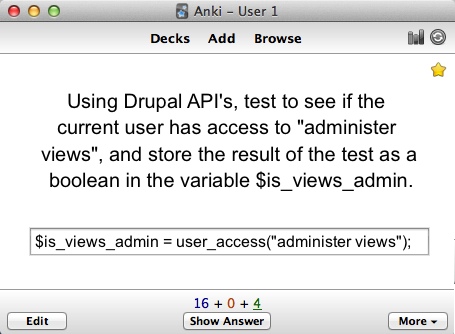

At it’s core, Anki lets me create flash cards. Each card has a front and a back. You simply put your question on one side and the answer on the other. There are a few variations on the format, like fill in the blank, etc. You can organize these cards into decks and tag them. Boring, right?

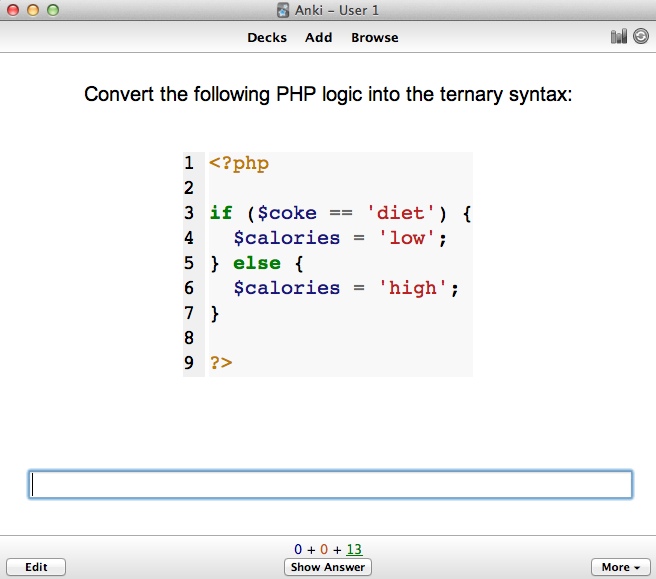

WRONG! Let’s look at one of my cards.

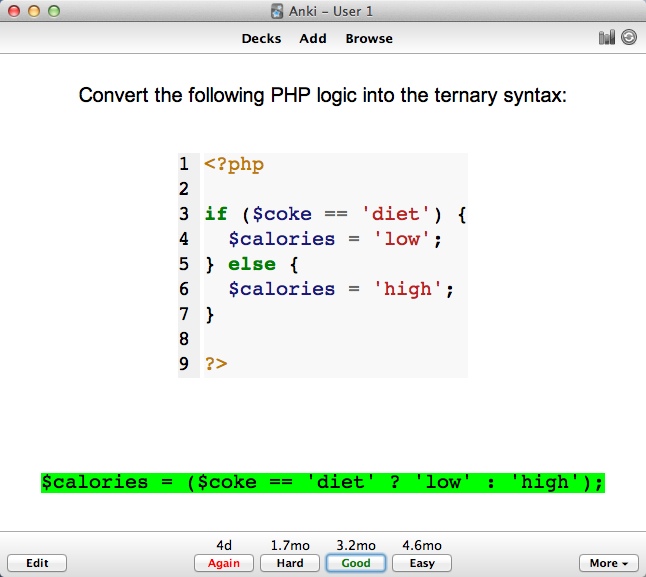

Ok, cool. We’ve got a little programming challenge and a text field where we can put our answer. Once I submit my answer, I get the following screen:

The yellow highlighting indicates that the answer I submitted was correct. However, instead of just sending this card to the bottom of the pile, Anki asks me to rate the difficulty of the question. If it was easy, then I don’t need to see the card for a while. If it was hard, then I should see it sooner. The time indicators above each of the buttons at the bottom tell me how long it will be until I see the card again.

As you can see, the lengths of time on this card are pretty long (4.6 months, if the question was easy). That’s because I’ve answered this question many times before. When a card is first created, reminders happen often because the knowledge is fresh and more likely to be forgotten without frequent reminders. Reminders decrease in frequency over time, and adjust as Anki learns which cards are easy or difficult for you (according to its learning algorithm).

Using this to learn Drupal

Lets be honest, you can’t completely learn Drupal just by answering flashcards. You need to be working on a Drupal instance, trying to build stuff with it, in order to get any kind of comprehensive understanding. But the Janki method shines at taking those discrete pieces of knowledge that you come across in the process, and ensuring that you remember them. That means fewer Google searches, less trips to api.drupal.org, and less context switching. If you’ve ever secretly wondered whether you were really a good Drupal developer, or just a good “Googler”, then the Janki method is one way to help you become the former.

That being said, you don’t just “do Janki” and call it good. If you go into it with the wrong technique, you could end up defeated. Here are a few techniques that I found to be helpful along the way.

1. Build your own cards.

Anki allows you to import & export cards, and since it has an open source community, it’s easy to find card sets online that other people have built. It may be tempting to download somebody else cards to kick off your study, but you’d be doing yourself a disservice. Why? Because when you make your own cards, you separate the initial learning of the concept from the remembering, which is important. You want to be in a situation where you aren’t needing to learn something new with every card you look at because it totally changes the experience. You’ll find yourself saying, “I have no clue what this answer is… yep, I wouldn’t have guessed that.” Compare that to, “Oh, man, I should know the answer to this one… shoot! I can’t believe I missed that!”. If you use somebody else’s cards, you find ones that are too easy, too hard, or not exactly relevant to your unique blend of skills and workflow. Finally, without giving context to your knowledge it’ll be more difficult to remember new information.

2. Make it a habit.

I work with Drupal nearly every day, so it was pretty easy for me to get in the habit of both writing and solving cards. For writing, I downloaded Anki for Mac onto my work computer so I could leave the application running on a separate Mac desktop during the day. Whenever I came across a new function or found a technique I wanted to remember, I’d hop over to Anki, add a new card, and hop back into my work.

As for solving, I downloaded Anki for Android, so I could solve cards on my smartphone whenever I had free moments during the day. While that seemed good, it didn’t really work because I was always more tempted to read RSS feeds, check Twitter, or do something else during my spare time. Instead, I recommend working it into a daily routine. I settled on a system where I needed to scan a barcode in the other room to turn off my alarm clock. Once the alarm turned off, my phone would automatically launch Anki, and I’d sit down and solve the three or four cards I needed to do for the day. Great for waking up the mind early in the day.

3. Write good questions.

Your learning is only as good as your questions. Bad questions will give away the answer in the wording of the question, or allow you to memorize the answer without understanding the concept. Good questions force you to understand the concept in order to solve them. It took some trial and error, but I started to learn what kinds of questions really worked well for me.

Use fill in the blank

The “Ternary” question above is a good example of this. Forcing yourself to write a line of code as an answer is good because you’re applying the exact knowledge you’ll need. I don’t need to memorize the “idea” of a ternary operation. I need to memorize the exact syntax because if I’m programming and I miss one semi-colon, my application breaks.

If I don’t force myself to write a line of code as an answer, I find myself clicking “Show Answer” before I’ve really committed to my answer. That leads to me “kind-of” getting it right, and “kind-of” learning it, which means I usually end up needing to google the exact syntax later.

Avoid True/False questions

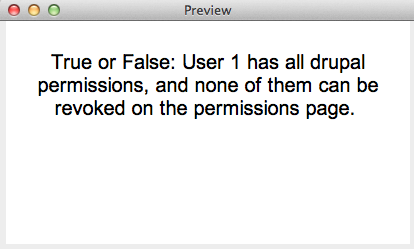

While I’m sure there are instances when these are appropriate, they tend to be less effective to me. It’s easy to word them poorly and make them easy to guess. For example, here’s one of my less-than-awesome True/False cards.

Seems like a good card right? The problem is that the very existence of this card makes it easy to guess the right answer. Why would I make this card if User 1’s permissions were revokable like anybody else’s? I wouldn’t, so the answer must be “True”. While it’s possible to write good True/False questions, it’s not easy, so I tend to stay away from them.

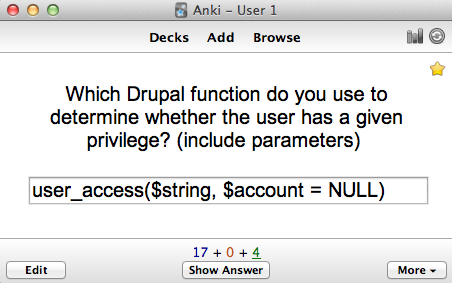

Don’t play “guess the parameters”

I thought it would be really cool to memorize the parameters of Drupal functions, and it is! However, the right way is to teach yourself how to apply the function (parameters included), instead of just guessing what the parameters are. Here’s an poor example:

This question forces me to memorize stuff that I won’t be need when I’m writing code later, like the words “string” and “account”. I think we could word this better:

There. Now we’re testing the same knowledge, but in the exact application that we’ll need in the future. That looks better.

Anything else?

I could mention more of Anki’s features, like its online plugin library or all the data and charts it produces (great for quantified self junkies), but I’ll leave you to explore more into it if you are interested. Here are a couple more articles about the Janki method, that were helpful for me along the way.

Whether you’ve been working with Drupal for 6 days or 6 years, there’s a lot left to learn. Using the Janki method has worked well for me, and I’d happily recommend it to anybody who is deliberately trying to learn Drupal, whether you’re working on mastering Drupal 7 or just getting started with Drupal 8.

UPDATE:

I’ve had several requests to see some of my cards and while I recommend you build your own, I do think that seeing somebody else’s may be useful as an example. Thus, I’ve included them at the link below. They’re not perfect, especially the early ones I made, but they may give you some ideas.